A Guide to the

Magnificent Bengal Cat

By C. Esmond Gay - Sarez Bengals - 2004

Sarah and I love all cats, but the Bengal has captivated us more than any other pedigree feline. We shouldn’t have favourites, but we’re mesmerised by this breed; they’re a study in contrasts… they emulate the wild look of the leopard cat, yet are as tender and as loving as a puppy - making them both beautiful and endearing companions. Having kept and bred all the colours and generations of the Bengal, this article contains much of the knowledge that we’ve gained over the years, and may help others to enjoy the pleasures of this awe-inspiring breed.

History of the Bengal Cat

With their sleek grace and astonishing spotted beauty, they could have stalked straight out of a steamy jungle. But Bengals, the mixed offspring of the domestic cat and the wild leopard cat, are perfectly at home prowling amongst garden roses and petunias.

Occie (F1 Male) -

Summer of 1994

The first written account of a possible leopard cat hybrid was in 1889 when Harrison Weir (considered to be the founder of the cat fancy) wrote in his book Our Cats and All about Them: “There is a rich-coloured tabby hybrid to be seen at the Zoological Society Gardens in Regents Park, between the wild cat of Bengal and a tabby she-cat. It is handsome, but very wild. These hybrids, I am told, will breed again with tame variety, or with others.” It is unclear if that was the first Bengal as Weir’s description of the wild parent is not precise.

Hybrids were mentioned again in 1927 in a magazine called Cat Gossip, when Cecil Boden-Kloss described how leopard cats and domestic cats were kept by Malay tribes, and he pondered as to whether they interbred.

The

first recorded attempt to mate a leopard cat and domestic cat was in

1934 and documented in a Belgian science journal, whilst in 1941 a

Japanese cat magazine wrote an article about another hybrid that was

being kept as a pet.

The

first recorded attempt to mate a leopard cat and domestic cat was in

1934 and documented in a Belgian science journal, whilst in 1941 a

Japanese cat magazine wrote an article about another hybrid that was

being kept as a pet.

Jean Mill (with Sarez

Amber) & Esmond Gay (with Sarez Leopard Legs) - Circa October

1995

Around the same time, several European zoos and research centres were also studying hybrids as there was a feline leukaemia outbreak in the early 1960s, and it was widely known that many wild cats are immune to this. Throughout that period and into the 1970s, there were other early pioneers hybridising from the leopard cat, one of the most prominent being William Engler, who is also accredited with officially naming the Bengal cat (derived from the taxonomic name of their wild forebear, Prionailurus bengalensis). However, despite the growing interest in hybrids, there was little concerted effort to develop the breed further. It would take a focussed lady to propel the breed forward - one who was determined to see the creation of a spotted pedigree cat…

When Jean Mill re-married, she moved to Southern California and then re-started her hybridising work in 1980 (Millwood Bengals), contacting Dr. Willard Centerwall in Riverside, who had produced F1s at Loma Linda University, California. He only needed these cats for their blood and then required suitable homes for them, and so he gave Jean Mill four female hybrids; Liquid Amber (75% wild blood), Favie (naturally, Jean Mill’s favourite), Shy Sister and Doughnuts. A little while later she acquired another five of Dr. Centerwall’s F1 females (but via another source), calling them Praline, Pennybank, Rorschach, Raisin Sunday and Wine Vinegar. If one looks at the pedigrees of most of today’s Bengals, many of these cats are there, right at the very beginning - fascinating.

One of Our Female

Leopard Cats - Summer of 1997

Jean Mill knew that the leopard cat is a genetically superior animal compared to the domestic cat and she didn’t want to weaken this attribute by using too many highly bred pedigree cats. And so, at the beginning of the 1980s, she and her husband went to India and obtained a rosetted domestic Indian Mau called Millwood Tory of Delhi… a cat who is now the ancestry of virtually all our Bengals.

During this foundation period, various other domestic breeds were used as outcrosses, but as there were so few hybridising leopard cats, inbreeding was common and the gene pool was tiny. So other cats were traced and used, including the fabled Bristol cat (now extinct due to fertility problems), which is a hybrid of the wild margay. Bengals from this particular lineage are said to be of a more robust type, have smaller ears than the norm, and have good rosettes.

At the beginning of the 1980s, other people such as Drs. Greg and Elizabeth Kent also became early Bengal breeders, mating leopard cats with Egyptian Maus. Like Jean Mills’, theirs was another very successful line and many modern Bengals can trace their roots back to the Kent’s cats.

In 1983, Jean Mill registered the first Bengal cat with The International Cat Association (TICA) as an experimental breed, and in 1986, TICA created the Bengal Breed Section and adopted the first breed standard. The Bengal is now TICA’s most popular registered breed.

The Bengal cat came to the United Kingdom around 1991, and my fiancée, Sarah, and I were amongst the first to own and breed them shortly after.

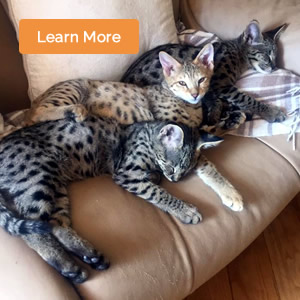

Various Generations of the Bengal Cat

The first three crosses from the leopard cat are referred to as F1, F2 and F3 Bengals - the “F” standing for filial which comes from the Latin word filius, meaning son, and in a genetic sense, refers to a sequence of generations following the parental generation. The numbers that follow denote the cat’s generation from the wild - these are important, as there are differences between them. All the generations including and after F4, are known as Stud Book Tradition (SBT) Bengals because once past this stage, there is very little difference between them.

The use of leopard cats (non-threatened subspecies only) is important to the breed as their undiluted wild blood strengthens and enlarges the Bengal’s relatively small gene pool. F1s are the rarest of the rare as they are complex to breed because the leopard cat is a wary, highly strung creature that’s notoriously difficult to handle. Any breeder wanting to hybridise must hand-rear them around domestic cats (and never near other wild cats), and even then, only about 1 in 15 leopard cats will mate with a domestic, as their inherent inclination is to do otherwise. Rearing and getting a leopard cat to hybridise is the hardest part of the process and very few individuals in the world have overcome the many hurdles and accomplished the great feat of breeding F1 Bengals.

To

date, only Sarah and I have been successful in hybridising in

Britain, and we’ve bred F1s not from just one of our leopard

cats, but from two -

first Sarez Little L.

in 2000, and then from Sarez Apollo in

2004.

To

date, only Sarah and I have been successful in hybridising in

Britain, and we’ve bred F1s not from just one of our leopard

cats, but from two -

first Sarez Little L.

in 2000, and then from Sarez Apollo in

2004.

Sarez Apollo (Leopard

Cat Stud) - Circa June 2003

And F2 kittens are just as challenging to breed because their mothers must be F1s and not the more manageable SBTs (due to the first three male generations being infertile). And so, even though the F1 x SBT mating process is easier, the heightened wild instincts of the F1 mothers means that the births of F2s can be fraught with danger. Even a docile F1 can kill or maim her kittens if she feels vaguely threatened, and some will not want humans near the babies at all - if that occurs, the kittens must be hand-reared from about four weeks old as socialisation in this generation is as essential if they are to grow up with good characters. Luckily for Sarah and me, our F1 mothers are very amenable. Because of their rarity, F2s can command high prices; in 1998, we sold an exceptional quality male called Kato (Sarez Allspots), for £25,000, giving him a place in the Guinness World Records.

Baby Gem (F1) &

Sarez Corai (Her F2) - Circa April 1996

F3s

retain some wild features, but one can see these traits diminishing

as their blood is diluted. SBTs lose some of the intriguing wild look

of the leopard cat, and the contrast between their background colour

and spots is less defined than in early generations (in the majority

of cases). The

temperament of SBTs is the same as a domestic cat, but even they

still retain a strong

air of nature about

them.

F3s

retain some wild features, but one can see these traits diminishing

as their blood is diluted. SBTs lose some of the intriguing wild look

of the leopard cat, and the contrast between their background colour

and spots is less defined than in early generations (in the majority

of cases). The

temperament of SBTs is the same as a domestic cat, but even they

still retain a strong

air of nature about

them.

F1s make ideal pets for knowledgeable cat fanatics who have enough time and energy to devote to them (Sarah and I only sell the males and never the F1 females that we breed, and own all but one in Britain). F2s also require similarly devoted homes. And for those who simply want an exotic, spotted cat that’s a little different, F3s and SBTs are the perfect cats. I love all the generations of the Bengal, but I am more drawn to F1s and F2s because my passion has always been for the wilder types of cats.

Michelle (F3) & Sarez Prince

(SBT Kitten) - Circa August 1995

Most

Popular Colours of the Bengal Cat

Most

Popular Colours of the Bengal Cat

Brown Spotted (Leopard): This colour mimics the coat of the leopard cat more than any other kind. There is a wide variance of colour intensity, with background colours that range from a silvery pearlescent grey to a sandy buff or a bright gold. Good quality coats have large rosettes and dark backward arrow shaped spots resembling thumbprints, covering their bodies. Their coats should have a lacquered sheen and their chests and bellies should be light coloured.

Leopardette Rajah (F3

Male) - Circa Feb. 1998

Sarez Snow King (F2

Male) - Circa Dec. 2002 Sarez Jubatus (F2

Male) - Circa Feb. 1998

Snow Marbles: They are a white variety of brown marbles and should have pearlescent backgrounds (including their chests and bellies) covered with dark rosettes and swirling patterns. For a long time, they were the rarest and most sought after breeding cat as they are the only variety that carries all of the main colours of the Bengal cat. As with the snow spotted, they develop their markings with age, and the variety comes in the same three colours listed under snow spotted.

Sarez Snow Bear (SBT

Stud) - Circa April 1996

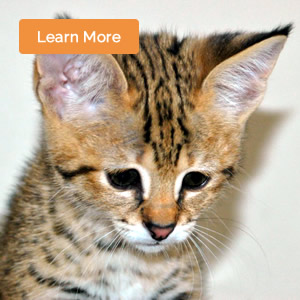

Physical Characteristics of the Bengal Cat

F1 Bengals tend to be smaller and leaner compared to their late generation counterparts, due to their closeness to the tiny leopard cat. Conversely, F2s can sometimes be far larger than the other generations, and this is due to the complex genetics of hybridisation. SBTs are also substantial animals and have one of the largest of the pedigree feline body types. All Bengal generations should have short tails, muscular chests, be sturdy boned and long in the torso. This body frame makes them flexible and provides a lot of leverage when running, rather like a leopard - Bengals are designed for speed, acceleration and power!

A nd

when standing or walking, all the Bengal generations angle their

bodies in a different way to other domestic cats, making them appear

far more regal. Even their gait differs, in that it’s more like

a trot or gallop - this is because they have slightly shorter front

legs and a raised hump, giving them the leopard’s stealthy,

stalking poise.

nd

when standing or walking, all the Bengal generations angle their

bodies in a different way to other domestic cats, making them appear

far more regal. Even their gait differs, in that it’s more like

a trot or gallop - this is because they have slightly shorter front

legs and a raised hump, giving them the leopard’s stealthy,

stalking poise.

Sarez

Mandawu (F2 Male) - Summer of 1998

Inherited from their wild forefathers, all good quality Bengals should have soft mink-like fur which makes them feel glorious to stroke, akin to caressing silk! Their coats should also sparkle as if they’ve been sprinkled with gold dust, a genetic trait passed down from one of Jean Mill’s early domestic foundation cats (Millwood Tory of Delhi). And quality cats should have a superb contrast between their markings and background colour.

In contrast, poor quality Bengals can have white ticking on their hairs, which is believed to originate from Abyssinian outcrosses, and this makes their coats feel rough to the touch and it blurs the definition of their markings.

The differences between good and poor quality coat types are immediately evident upon seeing and touching the cat, but naturally there are also other variances of each as well.

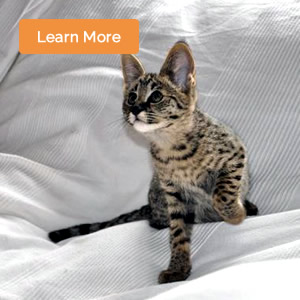

All generations have also inherited the wild cat’s camouflage coat, more commonly known as the fuzzies. These are long guard hairs that develop at about 3 weeks old and in the wild, they help young cubs to blend into the undergrowth, thus protecting them from predators. As they disguise the markings of Bengals too, one has to pick up and gently twist the kitten - this lifts the guard hairs up, and then from behind, one can see the background colour, the spots and how well defined they are. This gives a clear indication of what the kitten will look like at about 8 months old, when they grow out of this stage.

Personality Characteristics of the Bengal Cat

Forever refusing to conform to normal domestic cat rules, Bengals adore water and readily swim in ponds, pools or even in baths, just as the leopard cat does in rivers. Some of ours can even turn taps on! Bengals play in a different way to other domestic cats; they hunt their toys (or even their siblings) rather than merely playing with them, and they can be very protective over what they catch! Even their highly expressive voices are different to the meow of a domestic; it’s more the cry of a wild cat, but this is a trait that’s more noticeable in the earlier generations.

All Bengal generations have also inherited astounding intelligence from the leopard cat because their wild ancestors need to rely on their brains in order to survive in their hostile natural habitat. This enables Bengals to interact with humans on a higher level compared to other domestics, and it makes them more social, more loving, quicker witted and easier to train than other breeds.

Kitten Gay & Sarez

Pow Wow (75% Wild Blood F1 Female) - 24th May 2002

And due to their inherent cleverness, if taught from kittenhood, Bengals love to go out for walks on a harness and lead, trotting by their owners like little puppies. They also readily travel in a car with no cat carrier; just give them a nice comfortable lap to sit on, or perhaps the parcel shelf and they will contentedly sit there looking at the outside world!

Furthermore, young Bengals can be trained to fetch a toy that’s been thrown, and bring it back to their human companion - some of ours then pat our faces with their paws until Sarah or I throw it again… a game that can go on for hours, and I confirm that the human is likely to tire far quicker than the Bengal!

And

as they re-enact scenes reminiscent of the jungle, the athletic

prowess of this breed becomes evident as they leap from surface to

surface with such agility that they rarely knock anything over, and

so fleet footed that they seem to barely touch the ground!

And

as they re-enact scenes reminiscent of the jungle, the athletic

prowess of this breed becomes evident as they leap from surface to

surface with such agility that they rarely knock anything over, and

so fleet footed that they seem to barely touch the ground!

Baby Gem (F1 Female) -

2nd Half of 1995

It is the above physical and personality traits that makes this breed so captivating… from their features to their markings, from their stance to their prowl, from their intelligence to the way that they interact with humans… one always sees so much of their wild ancestors in the Bengal - more prominent in the filial generations, but still evident in the later ones.

Breeding from the Bengal Cat

SBT Sarez Bengal

Kittens (Four Colours) Including Sarez Natala (Far Right) &

Sarez Amber (Top Centre) - Circa August 1996 The

Bengal is a naturally robust and healthy cat due to the strong genes

passed down by their recent wild ancestors. The few problems that

exist within the breed have been brought in by outcrossing to other

domestic pedigrees such as Burmese and Abyssinian. They have

introduced flat chests, patella luxation and cleft palates as well as

more superficial faults such as ticking. However, such traits are

being bred out by using cats with known healthy backgrounds, by less

inbreeding and by using top quality cats.

The

Bengal is a naturally robust and healthy cat due to the strong genes

passed down by their recent wild ancestors. The few problems that

exist within the breed have been brought in by outcrossing to other

domestic pedigrees such as Burmese and Abyssinian. They have

introduced flat chests, patella luxation and cleft palates as well as

more superficial faults such as ticking. However, such traits are

being bred out by using cats with known healthy backgrounds, by less

inbreeding and by using top quality cats.

W hen

buying our breeding cats in the early to mid 1990s, Sarah and I chose

a broad variety of pedigrees for these reasons. The versatility that

such a diverse collection provides, results in healthier kittens with

fewer defects - and babies that predominantly carry all of the

colours of the Bengal cat. As such, we have bred the rarest of the

rare, not only generation-wise, but also in colour, including

Britain’s first F2 brown marbles, F2 snow marbles and F2 snow

spotted Bengals.

hen

buying our breeding cats in the early to mid 1990s, Sarah and I chose

a broad variety of pedigrees for these reasons. The versatility that

such a diverse collection provides, results in healthier kittens with

fewer defects - and babies that predominantly carry all of the

colours of the Bengal cat. As such, we have bred the rarest of the

rare, not only generation-wise, but also in colour, including

Britain’s first F2 brown marbles, F2 snow marbles and F2 snow

spotted Bengals.

Leopardette

(F1 Female) - Circa March 1995

Such socialisation is important otherwise the kittens grow up to be nervous and unloving. When we first started breeding, Bengals were so rare that we had to purchase two queens who had not been bred in a home environment, and to this day, one of those cats remains nervous, although with a lot of love, she has improved. And as far as pets are concerned, a cat’s personality is more important than a perfect appearance - a beautiful looking cat with a nasty nature is not going to make as good a pet as one of lesser quality with a loving character! But nowadays, one is able to get both in a kitten by seeking out good breeders.

Bringing Awareness to the Breed and Conservation

Sarah and I wanted to give something back and so using the income from our Bengals, we set up the Sarez Animal Rescue Sanctuary to give unwanted animals a good home, and we started the Sarez Wild Cat Conservation Programme in which we keep breeding pairs of African leopards, ocelots, servals and rarer subspecies of leopard cat. It is very rewarding to not only breed and keep some of the most stunning pedigree cats on earth, but also to help the endangered and the less fortunate creatures that inhabit our world.

A nd

the media are as fascinated with the Bengal as we are; our cats have

appeared on about 35

TV programmes and in over 100 national newspapers and magazines,

and have proven to be great ambassadors for

the breed. And our kittens have advertised

Armani, Versace and Cavalli haute

couture in

publications such as Vogue

Pelle, Tatler and Country Life. In

turn, this entices celebrities

to purchase our kittens, ranging from

Lord

Jeffrey Archer to Jonathan Ross,

and many others.

nd

the media are as fascinated with the Bengal as we are; our cats have

appeared on about 35

TV programmes and in over 100 national newspapers and magazines,

and have proven to be great ambassadors for

the breed. And our kittens have advertised

Armani, Versace and Cavalli haute

couture in

publications such as Vogue

Pelle, Tatler and Country Life. In

turn, this entices celebrities

to purchase our kittens, ranging from

Lord

Jeffrey Archer to Jonathan Ross,

and many others.

Sarez Secret

Recipie (F2 Female) - Circa March 1997

In certain areas we are close to this goal, for example the coats and markings of some SBTs are truly outstanding. But in others areas such as exactly replicating the mesmerising face of the wild cat, we are far from success. And personally, I feel that only the continued use of leopard cats and filial generations can help us to achieve this.

Bengals are the ultimate investment in art… they are the finest expressions of elegance and refinement - high-class cats that crave human affection, and that happily adapt to their owner’s way of life. No other pedigree cat has been blessed with the amazing qualities that Bengals possess. Style, beauty and a respect for the astounding creativity of man and nature combined… there’s no shortage of reasons for owning one of these cats…

C. Esmond Gay

Sarez Bengals

Copyright 2004 C. Esmond Gay

Dedicated to Baby Gem

Retirement Addition (2008)

Sarah and I achieved a phenomenal amount during the 11 years that we bred Bengals and many of our accomplishments are still unsurpassed. We obsessively chased every one of our goals and ambitions and didn’t stop until we had succeeded. And everything we did was meticulous and done to perfectionist standards.

However, this entailed working up to 18 hours a day, 7 days a week, and with few breaks or holidays. In hindsight, we did too much too fast because the enormous stress that we put ourselves under, plus looking after hundreds of animals almost single-handedly, took its toll on us mentally, emotionally and physically. By 2004, Sarah and I were suffering from severe exhaustion and so reluctantly, we retired. We hoped to lead a quieter life in Latin America, living and working with their endangered cats.

Our larger wild felines went to wildlife parks, our rescued animals went to sanctuaries and private homes, whilst many of our Bengals and leopard cats went to Pauline and Frank Turnock of Gayzette Bengals - they look after and nurture our cats, and are expanding the breeding programme that we worked so hard to create.

I stay in regular contact with Pauline and Frank and offer them my support and advice on the Bengal and wild cats. I follow their achievements, and behind the scenes, I am there for them and for the beautiful cats that we once so proudly owned.

To Sarah and me, our cats were more than just pets or breeding animals - they were our family. And within the articles I wrote, my deeply emotional descriptions of them and how they influenced our lives, portrays just how powerfully I love them; and so naturally, I feel terrible loss and miss them tremendously. However, I am grateful for the 11 wonderful years that they graced our home, and for the honour and privilege of being able to share part of my life with them… and for the amazing memories that they’ve left me with.

C. Esmond Gay